Interactions and Development: The Power of Connection

by Dr. Emily A. Snowden

A caregiver holds a young child while walking through a backyard garden.

We want our children to grow and be successful in this world—that’s a given. Whether that means your own children in traditional or new kinds of families, or for the childless (now and/or forever) for whom that just means the broader concept of children. Our children hold the hope of tomorrow for our families, our cultures, and our humanity.

It’s not a far leap from this hope for the future to believe that our children’s success in life is predictable based on how successful they are in school.

But, when we start to really define what that means, and I mean really—on the tip of a pin head—try to isolate those specific skills that will ensure their success later in life, it’s hard. Hard to even identify the knowledge and skills that sure success requires, but harder still to know if those we think are the most important now will become obsolete in the future.

Remember when our math teachers used to tell us “you won’t have a calculator in your pocket” when making us memorize our times tables? Who would’ve thought they were wrong.

Now, listen. Before this gets into a space where it sounds like I am “throwing the baby out with the bath water,” let me establish this—school is an incredibly important aspect of our modern culture. We learn explicit skills, social skills, self-regulatory skills, and critical thinking skills in school (or we should). These are important tools we need to exist in society today.

However, the “calculator in the pocket” issue looms—how do we really know what our children will need to know for the future? What makes us sure that their schooling—which they are investing hours in each day—is of the highest quality?

These questions are not easy to answer. Not for families, educators, researchers, system leaders, or policy makers. When we break this down even further to the “school readiness” skills needed to prepare our youngest children to enter the matrix of US compulsory schooling, it becomes even more difficult.

But, there is hope yet! Because one thing is directly available to us any time we have children in our care and it can mean everything to their success–our interactions.

What do you mean “interactions?”

Interactions are officially defined as “mutual or reciprocal action or influence.”

What does that actually mean? Our little moments together. Our conversations. Our rapid-fire, intuition-led responses to children. Our “in-the-moment” attempts to explain the world to our children as little pieces of it unfold in front of us.

Simply put, it’s found in those moments when they make a silly face, and we make one back, and then we both giggle at our vulnerability and ease together.

The mechanics of our interactions are often tone and language. We give children insight through the language we choose, and cues about how safe they are from the tone we offer those words in. In these interactions, we also work to teach them behaviors and values that fold them into our society, or “enculturate” them.

These interactions are quick–very quick. They’ve been compared to a ping pong game where the players are in a rapid exchange. It’s no wonder they’ve been officially labeled by Urie Bronfenbrenner as “serve and return.”

Bronfenbrenner’s Layers of Influence

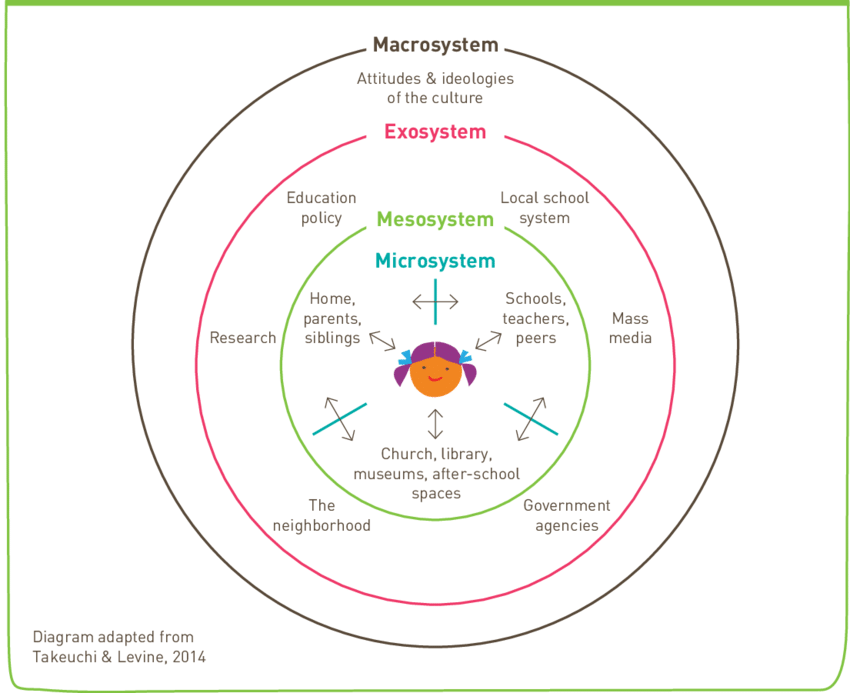

Urie Bronfenbrenner was an American psychologist whose work focused on understanding the complex relationships between who and what influences an individual’s development. To support his theory, he created the Bioecological Model (see image below) that labels the different layers of influence around each individual child.

Simply put, this model starts in the physical space where the child is, moves out through government policy and systems, and finally into the current time period. With this model, we are able to identify both the direct and indirect influences of the environment and of society on the individual. Within these circles, Bronfenbrenner also identifies who is present in interactions with or about the child. This includes families, teachers, peers, community members, policy makers, and members of their shared generation.

Bronfenbrenner’s microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Bronfenbrenners-ecological-systems-theory-8-10_fig1_313198613

When we directly care for and interact with children in these roles, we are in what Bronfenbrenner calls the “microsystem” or the closest circle of influence hugging each individual child. Here, we genuinely know them as a human.

This means we know who they are, what they like, what their voice sounds like, who their family members are. We know when their behavior constitutes a “good” day or an “off” day. We know when they’re tired and when they’re most engaged. We know their tendency to feel included or left out around certain peers, and we know when they are likely to eat their lunch and when they’re likely to not.

In the microsystem, we have access to genuine information about them and their individual needs and temperaments, and in this space we become important people who they form attachments to. As we interact with them as caregivers, children are wired to look to us for cues about their safety.

Bronfenbrenner emphasized the importance of interactions within these spheres of influence, with these direct interactions with a child being powerful drivers of development.

*NOTE: I’d like to acknowledge that while “Attachment Theory” has also been used in similar spaces and has many wonderful applications for caregivers, we also have a tendency to misunderstand “Attachment Theory” as only applicable to infants and their mothers. When this happens, it is common to slip into a conversation where we start to “blame” mothers for attachment issues instead of understanding the network of support they also need as they take on this new and all-consuming role. This is why it’s important to first build a foundational understanding of the “ecology” of the community context.

Interactions and Development

It has recently been established that infants actually sense our emotional states and experience more complex emotions than we previously believed to be possible. How? Through forming bonds and engaging interactions.

We know their brains invest significant resources in studying and knowing their caregivers’ faces. We also know that infants and their caregivers across cultures engage in “attunement play,” indicating that forming and tending to our bonds with our interactions is a part of our human experience.

An infant smiles as they gaze upon their caregiver’s face.

This is supported by neurological research that shows how these early interactions actually shape brain development. The impacts of these interactions have long-term benefits to the individual, too. Specifically, a systematic review of the literature found that “long-term associations between behaviors in early interactions and brain development outcomes were observed decades later.”

Why do our brains and nervous systems rely so much on interactions? To tell us that we’re safe. With these safety cues, we know we can relax, explore, and return to our “safe base” as needed.

Interactions in “Real Time”

It sounds nice and heartwarming doesn’t it? It’s as easy as just having interactions with them and maybe just keeping the yelling to a minimum…right? Not so. Not for parents and families, and not for educators either.

Families are dealing with real-life stress and often sleep deprivation during children’s early years. They’re changing diapers or potty training. They’re strapping children in and out of car seats in hot or cold cars. They’re facing a changing world and trying to grasp the idea of sending their children into it. They’re packing lunches and cutting food into bite-sized pieces. And again, wondering what knowledge and skills equip them to be successful.

Educators are also under real-life stress. Because they are famously underpaid and under-supported, this means they’re having to show up to an already challenging work environment with the baggage of debt, dental pain, and other stressors. And again, please never forget—this is far from a quiet or effortless place of work. All day you’re picking something up and putting it right back in a place you have already put it. You’re wiping down tables, wiping noses, sweeping, helping in the bathroom, opening lunches, and receiving multiple types of behaviors from children who need you in different ways.

Sigh. We are Sisyphus with the rock. We are tired. As we should be.

However, our children can sense when we are downhearted. They can sense in our tone whether they are safe or not. And that is why our interactions are everything.

So, what do we do?

Well, first we acknowledge the fast pace of the world we live in and how the systems we must participate in as adults can wear us down, particularly in the US where parents notably lack support like paid parental leave and access to affordable healthcare. This is not always something we can help (think Bronfenbrenner’s outer circles here). However, remembering the power of our presence and engagement with our children can be a beautiful remedy. It can also be a powerful preventative measure to make sure our children know life at a slower pace.

That said, sometimes we must simply slow down. Again, I know, an impossible task today. But, any moment we can, we must. In this modern world, rest is an act of revolution. When I say rest I mean we put our phones down and sit absolutely still and let being together be enough. We look at their faces when they talk to us and respond to them in whatever they bring us.

When they can’t slow down, we turn our eyes to what their eyes are looking at. We take a genuine interest in the activity that is captivating them. In this space, we have the wonderful privilege of asking them questions about how they see the world and letting them know that they are safe to answer. Here, we can share books or words or insights or activities or just the powerful medicine of silliness. This is when we laugh with them at the joy of jumping in rain puddles, even though we know it means we will be cleaning up a mess later.

When we can’t slow down, we give them real answers about the world we’re living in. We say things that are genuine even if they are firm, like “I can’t right now, but I will when I put this thing down,” “I know you are trying your best,” “I already answered that, but it sounds like you were hoping for a different answer,” or better yet, “I shouldn’t have lost my temper like that—I’m sorry.” We say “I always come back” and “I love who you are.”

A young child jumps in a rain puddle.

Today, with this great knowing that interactions are such a powerful determinant of lifelong success, we see promise in approaches like trauma-informed care. Increasingly, systems have begun to use interaction-based tools of ‘measurement’ when assessing the quality of early learning classrooms, as both small studies and large studies in the field continue to highlight the power of our bonds with young children.

Maybe our children can know a slower and kinder world. Maybe future generations can know meaningful, genuine connection in our modern “Age of Information.” Maybe our children could genuinely learn to love asking questions and exploring the world because it reminds them of the love they saw in our eyes when we supported them in those activities in their most formative years. Maybe they’ll know this so well that when they become caregivers their children will continue to be beneficiaries of our current investments of connection and presence.

I leave you today with a quote by the wonderful Lilian Katz, who puts this question of “success” in perspective:

“As you consider whether to move a child into formal academic training, remember that we want our children to do more than just learn how to read and write; we want them to learn in such a way that they become lifelong readers and writers. If we push our children to start learning these skills too far ahead of their own spontaneous interest and their capacity, we may sacrifice the long-range goal of having them enjoy such pursuits.”

Additional Resources

(Fred Rogers Institute) Simple Interactions https://www.fredrogersinstitute.org/simple-interactions

(Urie Bronfenbrenner) The Developing Ecology of Human Development https://youtu.be/xaQHgVaeKrc?si=1CQvuugTSlE2eIUj

(healthychildren.org) Parents of Young Children: Why Your Screen Time Matters, Too https://www.healthychildren.org/English/family-life/Media/Pages/Parents-of-Young-Children-Put-Down-Your-Smartphones.aspx

(Clarissa Pinkola Estes) Do Not Lose Heart, We Were Made for These Times https://www.dailygood.org/story/1538/do-not-lose-heart-we-were-made-for-these-times-clarissa-pinkola-estes/